Wow! This has been quite the exchange for a still-green blog like ours. I’m excited that seasoned blog vets and busy people like

Michael McCann and True Hoop’s

Henry Abbott took the time to respond. It’s great when basketball fans move outside the box, and box scores, to discuss meaningful issues that fall below the usual hardwood radar. To me, our conversation thrills more than any regular “who’s-the-next-Jordan” debate, and I’m thankful the

Internets act like techno-bartenders and help to facilitate our discussion in arenas beyond where the usual debates are confined. In the spirit of bartenders, I’d like to clink glasses again and continue our conversation by offering a response to the responses. Call it a meta-response on player autonomy but don’t try whistling at the same time.

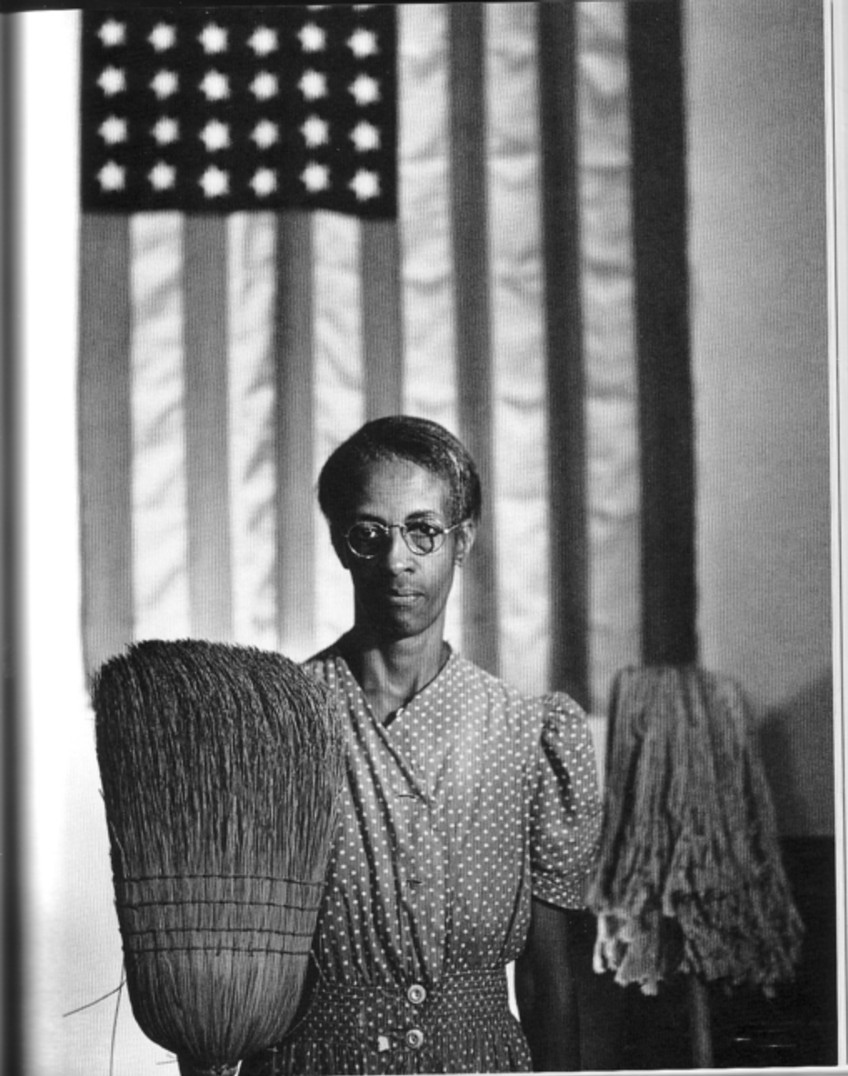

I want to begin with the last point McCann makes, mostly because True Hoop also took issue w ith it. Both disagree with the following comment I made in my review of McCann’s article: “I find it off-putting to employ the discourse of labor rights in a conversation about multi-million dollar athletes. I prefer to save the efficacy of that language for underpaid blue-collar laborers, undocumented immigrants, and sex workers—just to name a few.”

ith it. Both disagree with the following comment I made in my review of McCann’s article: “I find it off-putting to employ the discourse of labor rights in a conversation about multi-million dollar athletes. I prefer to save the efficacy of that language for underpaid blue-collar laborers, undocumented immigrants, and sex workers—just to name a few.”

True Hoop responds by writing, “There is not a rate of pay that makes exploitation OK. Wrong is wrong, and if it's wrong for an employer to test an employee's DNA, then it's wrong for the Bulls to test Eddy Curry's DNA, right?”

Well, sort of. I agree that exploitation is exploitation no matter which way the cheese is dealt. And I’m wrong to suggest that articulations of labor rights should be saved only for certain workers—as though labor rights were somehow like oil and in danger of running out if used too extravagantly.

That said, I also believe exploitation takes many different forms, and it doesn’t always mean the same thing. Exploitation, like autonomy, is situational, I suppose. For example, if my boss demanded I drop and give him twenty, I’d phone the EEOC; Eddy Curry probably wouldn’t. If my boss demanded celibacy, I’d cry foul; for others, celibacy is merely the flipside of living closer to God.

Which is all to say, I don’t think it’s necessarily wrong to test Curry’s DNA just because it’s wrong to test the DNA of telemarketers or cabbies or cat-sitters. The distinction here is the crux of McCann’s argument about the dress code, right? It’s why some in the sports world petition to wear suits and others protest them.

McCann responds to my point about labor rights by writing, “You are basically saying that the fact that these guys make a lot of money means their autonomy is not really a concern for you. Aren’t they still people or do they somehow become less human because they make a lot of money?”

Definitely still people, Professor—on that much, we agree.

In fact, I agree with you on the other point as well: the autonomy of NBA players isn’t really a concern for me. Luckily for them, it doesn’t have to be. The millions they make means they have access to resources most of us do not. These resources include lawyers, justice advocates, foundations, academics, Al Sharpton, the mainstream media—you name it.

What bothers me is that those folks most in danger of being exploited (e.g., blue-collar laborers, undocumented immigrants, sex workers, etc.) are also the people who lack the resources to prevent their exploitation. They don’t even have assistant coaches or trainers or ball boys, let alone legal counsel. That’s the reason why I think it’s socially irresponsible to discuss the labor rights of multi-million dollar athletes without considering the human rights of people on minimum wage.

McCann also asks, “is it their wealth as much as who they are that bothers you: would you feel the same way about Bill Gates as you do about Allen Iverson?”

McCann also asks, “is it their wealth as much as who they are that bothers you: would you feel the same way about Bill Gates as you do about Allen Iverson?”

Yes, I do feel the same way about Bill Gates—billions of times more so, in fact. That much wealth in the hands of one person, whether Paul Allen or Malik Allen, irritates me to no end. Frankly, I’m surprised you don’t agree with me.

The autonomy of all of us is eroded when wealth is distributed unequally, Professor, especially in a country where health care is directly tied to how much money you make. Fixing the problem is structural (which is why Gates and the NBA can donate so much cash and so many sneakers, and still dissatisfy me), of course, but it also demands that Gates and Iverson take pay-cuts.

Next time you’re in Los Angeles, Professor, take a ride by the old Forum in Inglewood. Don’t you think there are material connections between the spectacular economy of the Showtime Lakers and Inglewood’s economy of unemployment and blight? My man Magic knows this. Cassius realized and became Muhammad. Even Iverson has come to understand.

As much as I root for the Lakers, I save my advocacy for those who don’t play under lights. You dig?

McCann also corrects me by saying that his statistics were verified by the dudes in suits at ESPN. Fair enough. I care more about the stats of my fantasy basketball team anyway.

As for McCann’s definition of the term “autonomy,” well, it still remains hazy (or “amorphous,” as McCann puts it). I suppose it has to for his argument to have traction.

McCann cites another example of the erosion of player autonomy in his response: the rookie draft. To be fair, I’ll quote the paragraph in full before I respond: “First off, consider that some would argue the draft itself is an infringement on player autonomy. Players have to play for a particular team in a particular city, neither of which they may like, and the only alternative would be to play minor league hoops or play in Europe; it’s like being a law student at UCLA and planning to practice in L.A., but then there is a law firm draft and you get picked by a law firm in Bismarck North Dakota, and have to stay there for at least four years or you can’t practice law in the U.S. (or at least practice law in the U.S. without having to give up 95% of your salary). For related commentary on this, check out Alan Milstein’s post Reggie Bush Sweepstakes from last December.”

If I follow his point correctly, the fact some players call Staples home while others are forced to live near Charlotte is proof the players are losing their autonomy. Dude, you stagger me.

near Charlotte is proof the players are losing their autonomy. Dude, you stagger me.

Many high-profile jobs require that employees live in certain areas. For instance, if a college student from Bismarck really wants to work in publishing, he’ll probably have to say goodbye Dakota, hello New York. That’s the breaks. Part of choosing a profession requires decisions like these. I’m guessing most ballers decide early on that the perks of cheerleaders and paychecks outweigh the bummers of relocation. Autonomy has nothing to do with it.

When we choose career paths, we also make decisions about the desirability of the lifestyle (sorry, I hate that word too) that comes with the job. That’s why not everyone with charisma and smarts wants to be a law professor. And not everyone with size wants to be a bodyguard or a cop.

Ideally, I suppose, we’d all have our choice of profession, region, dress code, wage, and qualifications. It kind of just seems like that’s not really possible, no? And if it is, Scalabrine’s contract probably isn’t moving us any closer, right? Might even be setting us back.

McCann’s argument about the erosion of autonomy implies that all social contracts reduce the autonomy of those who enter into them. McCann would have us believe that signing million-dollar deals doesn’t realize or empower player autonomy but erodes it. I find that difficult to believe. Just as Ben Wallace knew about Skiles’s rules before he signed with the Bulls, athletes know about Stern’s when they declare their dreams.

Yes, Marcus Camby might hate wearing a suit, and sure, he didn’t bargain for it when he picked up the ball long ago. But, wearing a suit to work doesn’t mean he’s up against the Leviathan—especially with $9.3 mil in his double-breasted pockets.

Leviathan—especially with $9.3 mil in his double-breasted pockets.

Question: How many sweatbands must an NBA athlete buy before he goes bankrupt?

Answer: I’m more concerned with the people in sweatshops making all of those sweatbands.

Aren’t you?

Etan Thomas’s recent column for Slam Online recounts what he believes was an example of racism in the NBA. In my opinion, the incident seems unworthy of the reading he provides—i.e., the ref’s comment seems more anti-jock than anti-black. In fact, the ref probably isn’t even anti-jock (why work ballgames if you can’t stand muscle?) so much as stupid and avuncular.

Etan Thomas’s recent column for Slam Online recounts what he believes was an example of racism in the NBA. In my opinion, the incident seems unworthy of the reading he provides—i.e., the ref’s comment seems more anti-jock than anti-black. In fact, the ref probably isn’t even anti-jock (why work ballgames if you can’t stand muscle?) so much as stupid and avuncular. It’s why you can teach Kate Chopin in New Haven for the rest of your life and still not understand what a fourteen-year-old boy from the 9th Ward might know about New Orleans.

at’s why the ref made the stupid joke in the first place, failing to imagine how Thomas’s race might lead him to view the encounter differently—perhaps even more accurately.

at’s why the ref made the stupid joke in the first place, failing to imagine how Thomas’s race might lead him to view the encounter differently—perhaps even more accurately.